Which Item Serves As The Mascot For Pixar Animation Studios?

| | |

Headquarters in Emeryville, California | |

| Blazon | Subsidiary |

|---|---|

| Manufacture | Animation |

| Predecessor | The Graphics Group of Lucasfilm Figurer Division (1979–1986) |

| Founded | Feb 3, 1986 (1986-02-03) in Richmond, California |

| Founders |

|

| Headquarters | 1200 Park Avenue, Emeryville, California United states of america |

| Area served | Worldwide |

| Key people |

|

| Products | Calculator animations |

| Brands |

|

| Owner | Steve Jobs (1986–2006) |

| Number of employees | 1,233 (2020) |

| Parent | Walt Disney Studios (2006–present) |

| Website | pixar |

| Footnotes / references [1] [2] [iii] | |

Pixar Blitheness Studios (), ordinarily known as just Pixar, is an American estimator animation studio known for its critically and commercially successful computer animated feature films. Information technology is based in Emeryville, California, and is a subsidiary of Walt Disney Studios, which is owned past The Walt Disney Company.

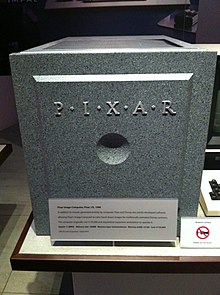

Pixar began in 1979 as role of the Lucasfilm computer division, known every bit the Graphics Group, before its spin-off equally a corporation in 1986, with funding from Apple co-founder Steve Jobs, who became its bulk shareholder.[two] Disney purchased Pixar in 2006 at a valuation of $7.four+ billion by converting each share of Pixar stock to two.iii shares of Disney stock.[4] [5] Pixar is best known for its feature films, technologically powered by RenderMan, the company'southward own implementation of the industry-standard RenderMan Interface Specification image-rendering awarding programming interface. The studio'south mascot is Luxo Jr., a desk lamp from the studio's 1986 brusk film of the same name.

Pixar has produced 25 feature films, beginning with Toy Story (1995), which is the first fully computer-animated feature film; its near recent film was Turning Red (2022). The studio has also produced many short films. As of July 2019[update], its feature films accept earned approximately $14 billion at the worldwide box office,[6] with an boilerplate worldwide gross of $680 meg per film.[seven] Toy Story iii (2010), Finding Dory (2016), Incredibles 2 (2018), and Toy Story four (2019) are all among the l highest-grossing films of all time, with Incredibles 2 being the fourth highest-grossing blithe film of all fourth dimension, with a gross of $1.ii billion; the other 3 as well grossed over $ane billion. Moreover, 15 of Pixar'southward films are in the l highest-grossing blithe films of all time.

The studio has earned 23 Academy Awards, 10 Gilt Earth Awards, and 11 Grammy Awards, along with numerous other awards and acknowledgments. Many of Pixar's films take been nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, since its inauguration in 2001, with eleven winners being Finding Nemo (2003), The Incredibles (2004), Ratatouille (2007), WALL-E (2008), Upward (2009), Toy Story iii (2010), Dauntless (2012), Inside Out (2015), Coco (2017), Toy Story 4 (2019), and Soul (2020); the five nominated without winning are Monsters, Inc. (2001), Cars (2006), Incredibles 2 (2018), Onward (2020), and Luca (2021). Upwards and Toy Story 3 were likewise nominated for the more competitive and inclusive University Award for All-time Movie.

On February 10, 2009, Pixar executives John Lasseter, Brad Bird, Pete Docter, Andrew Stanton, and Lee Unkrich were presented with the Golden Lion award for Lifetime Achievement by the Venice Film Festival. The concrete laurels was ceremoniously handed to Lucasfilm's founder, George Lucas.

History [edit]

Early on history [edit]

Pixar got its commencement in 1974 when New York Institute of Engineering science'due south (NYIT) founder, Alexander Schure, who was also the owner of a traditional animation studio, established the Reckoner Graphics Lab (CGL) and recruited computer scientists who shared his ambitions nigh creating the world's get-go computer-blithe film. Edwin Catmull and Malcolm Blanchard were the showtime to be hired and were soon joined by Alvy Ray Smith and David DiFrancesco some months after, which were the four original members of the Computer Graphics Lab, located in a converted two-story garage caused from the former Vanderbilt-Whitney manor.[8] [9] Schure kept pouring money into the computer graphics lab, an estimated $fifteen one thousand thousand, giving the group everything they desired and driving NYIT into serious fiscal troubles.[10] Eventually, the group realized they needed to piece of work in a real movie studio in guild to achieve their goal. Francis Ford Coppola then invited Smith to his house for a iii-twenty-four hours media conference, where Coppola and George Lucas shared their visions for the future of digital moviemaking.[xi]

When Lucas approached them and offered them a job at his studio, vi employees moved to Lucasfilm. During the following months, they gradually resigned from CGL, constitute temporary jobs for well-nigh a twelvemonth to avert making Schure suspicious, and joined the Graphics Group at Lucasfilm.[12] [13] The Graphics Group, which was one-3rd of the Figurer Division of Lucasfilm, was launched in 1979 with the hiring of Catmull from NYIT,[14] where he was in charge of the Figurer Graphics Lab. He was then reunited with Smith, who also fabricated the journey from NYIT to Lucasfilm, and was made the director of the Graphics Grouping. At NYIT, the researchers pioneered many of the CG foundation techniques—in item, the invention of the alpha channel past Catmull and Smith.[15] Over the next several years, the CGL would produce a few frames of an experimental movie called The Works. Subsequently moving to Lucasfilm, the squad worked on creating the precursor to RenderMan, called REYES (for "renders everything you e'er saw") and developed several critical technologies for CG—including particle furnishings and various animation tools.[xvi]

John Lasseter was hired to the Lucasfilm squad for a week in tardily 1983 with the title "interface designer"; he animated the short film The Adventures of André & Wally B. [17] In the side by side few years, a designer suggested naming a new digital compositing computer the "Picture Maker". Smith suggested that the laser-based device have a catchier name, and came upward with "Pixer", which after a coming together was changed to "Pixar".[eighteen]

In 1982, the Pixar squad began working on special-effects film sequences with Industrial Light & Magic. After years of enquiry, and key milestones such as the Genesis Effect in Star Trek Ii: The Wrath of Khan and the Stained Glass Knight in Immature Sherlock Holmes,[xiv] the group, which so numbered forty individuals, was spun out as a corporation in Feb 1986 by Catmull and Smith. Amidst the 38 remaining employees, there were also Malcolm Blanchard, David DiFrancesco, Ralph Guggenheim, and Nib Reeves, who had been part of the squad since the days of NYIT. Tom Duff, also an NYIT member, would later join Pixar afterwards its formation.[2] With Lucas'due south 1983 divorce, which coincided with the sudden dropoff in revenues from Star Wars licenses following the release of Render of the Jedi, they knew he would near likely sell the whole Graphics Group. Worried that the employees would be lost to them if that happened, which would preclude the creation of the first calculator-blithe flick, they concluded that the best fashion to keep the team together was to plow the grouping into an independent company. Just Moore'south Law also suggested that sufficient computing power for the first film was still some years away, and they needed to focus on a proper product until then. Eventually, they decided they should be a hardware company in the meantime, with their Pixar Image Computer as the core product, a system primarily sold to governmental, scientific, and medical markets.[two] [x] [nineteen] They also used SGI computers.[20]

In 1983, Nolan Bushnell founded a new reckoner-guided blitheness studio chosen Kadabrascope every bit a subsidiary of his Chuck E. Cheese's Pizza Time Theatres company (PTT), which was founded in 1977. Only one major project was made out of the new studio, an animated Christmas special for NBC starring Chuck Due east. Cheese and other PTT mascots; known every bit "Chuck Eastward. Cheese: The Christmas That Almost Wasn't". The animation move would be fabricated using tweening instead of traditional cel animation. After the video game crash of 1983, Bushnell started selling some subsidiaries of PTT to keep the business organisation afloat. Sente Technologies (another sectionalization, was founded to have games distributed in PTT stores) was sold to Bally Games and Kadabrascope was sold to Lucasfilm. The Kadabrascope assets were combined with the Reckoner Division of Lucasfilm.[21] Coincidentally, ane of Steve Jobs's beginning jobs was under Bushnell in 1973 as a technician at his other visitor Atari, which Bushnell sold to Warner Communications in 1976 to focus on PTT.[22] PTT would after get bankrupt in 1984 and be acquired past ShowBiz Pizza Identify.[23]

Contained company (1986–1999) [edit]

In 1986, the newly independent Pixar was headed past President Edwin Catmull and Executive Vice President Alvy Ray Smith. Lucas's search for investors led to an offering from Steve Jobs, which Lucas initially found as well low. He eventually accustomed subsequently determining it impossible to find other investors. At that signal, Smith and Catmull had been declined 45 times, and 35 venture capitalists and 10 large corporations had declined.[24] Jobs, who had been edged out of Apple tree in 1985,[two] was now founder and CEO of the new computer company Side by side. On February 3, 1986, he paid $5 million of his own coin to George Lucas for technology rights and invested $five million cash as uppercase into the visitor, joining the lath of directors equally chairman.[2] [25]

In 1985, while still at Lucasfilm, they had made a deal with the Japanese publisher Shogakukan to make a estimator-blithe picture called Monkey, based on the Monkey King. The project continued sometime later they became a carve up visitor in 1986, but information technology became clear that the technology was non sufficiently advanced. The computers were non powerful enough and the budget would exist too high. Then they focused on the calculator hardware business for years until a computer-animated feature became feasible according to Moore'southward law.[26] [27]

At the time, Walt Disney Studios was interested and somewhen bought and used the Pixar Image Computer and custom software written past Pixar as function of its Figurer Animation Product Organization (CAPS) projection, to migrate the laborious ink and paint part of the 2D animation procedure to a more automated method. The company's commencement feature film to be released using this new animation method was The Rescuers Downward Nether (1990).[28] [29]

In a bid to bulldoze sales of the arrangement and increment the company'south uppercase, Jobs suggested releasing the product to the mainstream market. Pixar employee John Lasseter, who had long been working on not-for-turn a profit curt demonstration animations, such as Luxo Jr. (1986) to show off the device's capabilities, premiered his creations to great fanfare at SIGGRAPH, the computer graphics industry'due south largest convention.[thirty]

Nonetheless, the Epitome Reckoner had inadequate sales[xxx] which threatened to end the company every bit financial losses grew. Jobs increased investment in substitution for an increased stake, reducing the proportion of management and employee ownership until somewhen, his full investment of $fifty one thousand thousand gave him command of the entire company. In 1989, Lasseter's growing blitheness section, originally composed of just four people (Lasseter, Bill Reeves, Eben Ostby, and Sam Leffler), was turned into a division that produced figurer-animated commercials for outside companies.[i] [31] [32] In Apr 1990, Pixar sold its hardware division, including all proprietary hardware technology and imaging software, to Vicom Systems, and transferred 18 of Pixar's approximately 100 employees. That year, Pixar moved from San Rafael to Richmond, California.[33] Pixar released some of its software tools on the open up market for Macintosh and Windows systems. RenderMan is one of the leading 3D packages of the early 1990s, and Typestry is a special-purpose 3D text renderer that competed with RayDream.[ citation needed ]

During this flow, Pixar connected its successful relationship with Walt Disney Feature Animation, a studio whose corporate parent would ultimately go its most important partner. As 1991 began, however, the layoff of thirty employees in the company's computer hardware department—including the company's president, Chuck Kolstad,[34] reduced the total number of employees to just 42, approximately its original number.[35] Pixar made a historic $26 million bargain with Disney to produce 3 computer-animated feature films, the first of which was Toy Story, the production of the technological limitations that challenged CGI.[36] Past then the software programmers, who were doing RenderMan and IceMan, and Lasseter's blitheness department, which made television commercials (and iv Luxo Jr. shorts for Sesame Street the same yr), were all that remained of Pixar.[37]

Even with income from these projects, the visitor continued to lose money and Steve Jobs, equally chairman of the board and now the total owner, often considered selling information technology. Even every bit late equally 1994, Jobs contemplated selling Pixar to other companies such as Hallmark Cards, Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, and Oracle CEO and co-founder Larry Ellison.[38] Only afterwards learning from New York critics that Toy Story would probably be a hit—and confirming that Disney would distribute it for the 1995 Christmas season—did he decide to give Pixar another risk.[39] [40] For the first time, he also took an agile leadership role in the visitor and made himself CEO.[ citation needed ] Toy Story grossed more $373 meg worldwide[41] and, when Pixar held its initial public offer on November 29, 1995, it exceeded Netscape's as the biggest IPO of the yr. In its start half-hour of trading, Pixar stock shot from $22 to $45, delaying trading because of unmatched purchase orders. Shares climbed to US$49 and closed the solar day at $39.[42]

During the 1990s and 2000s, Pixar gradually developed the "Pixar Braintrust", the studio'south primary creative development process, in which all of its directors, writers, and lead storyboard artists regularly examine each other'southward projects and give very candid "notes", the manufacture term for constructive criticism.[43] The Braintrust operates under a philosophy of a "filmmaker-driven studio", in which creatives assistance each other move their films forward through a process somewhat like peer review, equally opposed to the traditional Hollywood arroyo of an "executive-driven studio" in which directors are micromanaged through "mandatory notes" from development executives outranking the producers.[44] [45] According to Catmull, information technology evolved out of the working relationship between Lasseter, Stanton, Docter, Unkrich, and Joe Ranft on Toy Story.[43]

Every bit a result of the success of Toy Story, Pixar built a new studio at the Emeryville campus which was designed by PWP Mural Architecture and opened in November 2000.[ citation needed ]

Collaboration with Disney (1999–2006) [edit]

Pixar and Disney had disagreements over the production of Toy Story 2. Originally intended as a straight-to-video release (and thus non part of Pixar'south three-picture deal), the film was eventually upgraded to a theatrical release during production. Pixar demanded that the film then be counted toward the three-flick understanding, only Disney refused.[46] Though profitable for both, Pixar later complained that the arrangement was not equitable. Pixar was responsible for creation and production, while Disney handled marketing and distribution. Profits and production costs were split as, but Disney exclusively endemic all story, character, and sequel rights and also collected a x- to 15-percent distribution fee. The lack of these rights was perhaps the nearly onerous aspect for Pixar and precipitated a contentious relationship.[ commendation needed ]

The two companies attempted to reach a new agreement for 10 months and failed on Jan 26, 2001, July 26, 2002, Apr 22, 2003, January xvi, 2004, July 22, 2004, and January 14, 2005. The new deal would exist simply for distribution, every bit Pixar intended to control production and own the resulting story, character, and sequel rights while Disney would ain the right of first refusal to distribute any sequels. Pixar likewise wanted to finance its own films and collect 100 pct turn a profit, paying Disney only the 10- to fifteen-per centum distribution fee.[47] More than chiefly, as part of any distribution agreement with Disney, Pixar demanded control over films already in production under the old understanding, including The Incredibles (2004) and Cars (2006). Disney considered these conditions unacceptable, just Pixar would not concede.[47]

Disagreements between Steve Jobs and Disney chairman and CEO Michael Eisner made the negotiations more difficult than they otherwise might take been. They broke down completely in mid-2004, with Disney forming Circle Seven Blitheness and Jobs declaring that Pixar was actively seeking partners other than Disney.[48] Fifty-fifty with this announcement and several talks with Warner Bros., Sony Pictures, and 20th Century Fox, Pixar did not enter negotiations with other distributors,[49] although a Warner Bros. spokesperson told CNN, "We would love to be in business with Pixar. They are a corking visitor."[47] Afterward a lengthy hiatus, negotiations between the ii companies resumed following the departure of Eisner from Disney in September 2005. In preparation for potential fallout between Pixar and Disney, Jobs announced in late 2004 that Pixar would no longer release movies at the Disney-dictated November time frame, just during the more lucrative early on summer months. This would also allow Pixar to release DVDs for its major releases during the Christmas shopping season. An added benefit of delaying Cars from November iv, 2005, to June 9, 2006, was to extend the time frame remaining on the Pixar-Disney contract, to see how things would play out between the two companies.[49]

Pending the Disney acquisition of Pixar, the ii companies created a distribution deal for the intended 2007 release of Ratatouille, to ensure that if the conquering failed, this one moving picture would exist released through Disney's distribution channels. In contrast to the earlier Pixar bargain, Ratatouille was meant to remain a Pixar property and Disney would have received only a distribution fee. The completion of Disney'southward Pixar conquering, however, nullified this distribution arrangement.[50]

Walt Disney Studios subsidiary (2006–present) [edit]

In January 2006, Disney ultimately agreed to purchase Pixar for approximately $7.4 billion in an all-stock deal.[51] Following Pixar shareholder approval, the acquisition was completed May 5, 2006. The transaction catapulted Jobs, who owned 49.65% of total share interest in Pixar, to Disney's largest private shareholder with 7%, valued at $3.9 billion, and a new seat on its board of directors.[5] [52] Jobs's new Disney holdings exceeded holdings belonging to ex-CEO Michael Eisner, the previous top shareholder, who still held 1.7%; and Disney Managing director Emeritus Roy East. Disney, who held well-nigh ane% of the corporation'southward shares. Pixar shareholders received 2.3 shares of Disney common stock for each share of Pixar mutual stock redeemed.[ citation needed ]

As part of the deal, John Lasseter, by then Executive Vice President, became Principal Creative Officeholder (reporting directly to president and CEO Robert Iger and consulting with Disney Manager Roy E. Disney) of both Pixar and Walt Disney Animation Studios (including its division DisneyToon Studios), likewise equally the Master Artistic Adviser at Walt Disney Imagineering, which designs and builds the visitor's theme parks.[52] Catmull retained his position every bit President of Pixar, while also becoming President of Walt Disney Animation Studios, reporting to Iger and Dick Cook, chairman of the Walt Disney Studios. Jobs's position as Pixar'due south chairman and chief executive officeholder was abolished, and instead, he took a identify on the Disney board of directors.[53]

Later the deal closed in May 2006, Lasseter revealed that Iger had realized Disney needed to buy Pixar while watching a parade at the opening of Hong Kong Disneyland in September 2005.[54] Iger noticed that of all the Disney characters in the parade, not one was a character that Disney had created within the final ten years since all the newer ones had been created by Pixar.[54] Upon returning to Burbank, Iger commissioned a fiscal analysis that confirmed that Disney had actually lost money on animation for the past decade, and then presented that data to the board of directors at his kickoff board meeting after being promoted from COO to CEO, and the board, in plow, authorized him to explore the possibility of a deal with Pixar.[55] Lasseter and Catmull were wary when the topic of Disney buying Pixar kickoff came upwards, but Jobs asked them to give Iger a take chances (based on his own experience negotiating with Iger in summer 2005 for the rights to ABC shows for the 5th-generation iPod Classic),[56] and in turn, Iger convinced them of the sincerity of his epiphany that Disney really needed to re-focus on animation.[54]

Lasseter and Catmull's oversight of both the Disney Feature Blitheness and Pixar studios did not mean that the two studios were merging, all the same. In fact, additional conditions were laid out as part of the deal to ensure that Pixar remained a separate entity, a business organization that analysts had expressed near the Disney deal.[57] [ folio needed ] Some of those weather were that Pixar 60 minutes policies would remain intact, including the lack of employment contracts. As well, the Pixar proper noun was guaranteed to continue, and the studio would remain in its electric current Emeryville, California, location with the "Pixar" sign. Finally, branding of films made mail service-merger would exist "Disney•Pixar" (get-go with Cars).[58]

Jim Morris, producer of WALL-Eastward (2008), became general director of Pixar. In this new position, Morris took charge of the day-to-day running of the studio facilities and products.[59]

After a few years, Lasseter and Catmull were able to successfully transfer the basic principles of the Pixar Braintrust to Disney Animation, although meetings of the Disney Story Trust are reportedly "more than polite" than those of the Pixar Braintrust.[60] Catmull later on explained that afterward the merger, to maintain the studios' split up identities and cultures (notwithstanding the fact of common ownership and common senior management), he and Lasseter "drew a hard line" that each studio was solely responsible for its ain projects and would not exist allowed to infringe personnel from or lend tasks out to the other.[61] [62] That rule ensures that each studio maintains "local buying" of projects and can be proud of its own work.[61] [62] Thus, for example, when Pixar had problems with Ratatouille and Disney Animation had problems with Bolt (2008), "nobody bailed them out" and each studio was required "to solve the trouble on its own" fifty-fifty when they knew there were personnel at the other studio who theoretically could take helped.[61] [62]

Expansion [edit]

On Apr 20, 2010, Pixar opened Pixar Canada in the downtown area of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.[63] The roughly two,000 square meters studio produced seven curt films based on Toy Story and Cars characters. In October 2013, the studio was closed downwardly to refocus Pixar'south efforts at its main headquarters.[64]

In November 2014, Morris was promoted to president of Pixar, while his counterpart at Disney Animation, general manager Andrew Millstein, was besides promoted to president of that studio.[65] Both connected to study to Catmull, who retained the title of president of both Disney Animation and Pixar.[65]

On November 21, 2017, Lasseter appear that he was taking a six-month leave of absenteeism after acknowledging what he called "missteps" in his beliefs with employees in a memo to staff. According to The Hollywood Reporter and The Washington Post, Lasseter had a history of declared sexual misconduct towards employees.[66] [67] [68] On June viii, 2018, it was appear that Lasseter would leave Disney Animation and Pixar at the finish of the yr, merely would take on a consulting function until then.[69] Pete Docter was announced every bit Lasseter's replacement as main artistic officer of Pixar on June 19, 2018.[seventy]

Reconstruction and continuing expansion [edit]

On October 23, 2018, it was announced that Catmull would be retiring. He stayed in an adviser role until July 2019.[71] On January 18, 2019, information technology was announced that Lee Unkrich would be leaving Pixar after 25 years.[72]

Campus [edit]

The Steve Jobs Building at the Pixar campus in Emeryville

The atrium of the Pixar campus

When Steve Jobs, principal executive officer of Apple Inc. and Pixar, and John Lasseter, so-executive vice president of Pixar, decided to motion their studios from a leased space in Indicate Richmond, California, to larger quarters of their own, they chose a 20-acre site in Emeryville, California,[73] formerly occupied by Del Monte Foods, Inc. The first of several buildings, the high-tech structure designed past Bohlin Cywinski Jackson[74] has special foundations and electricity generators to ensure connected film production, even through major earthquakes. The graphic symbol of the building is intended to abstractly call back Emeryville's industrial past. The two-story steel-and-masonry building is a collaborative space with many pathways.[75]

The digital revolution in filmmaking was driven past practical mathematics, including computational physics and geometry.[76] In 2008, this led Pixar senior scientist Tony DeRose to offer to host the second Julia Robinson Mathematics Festival at the Emeryville campus.[77]

Characteristic films and shorts [edit]

Traditions [edit]

Some of Pixar's kickoff animators were one-time cel animators including John Lasseter, and others came from computer blitheness or were fresh higher graduates.[78] A big number of animators that make up its animation section had been hired around the releases of A Bug's Life (1998), Monsters, Inc. (2001), and Finding Nemo (2003). The success of Toy Story (1995) made Pixar the get-go major calculator-blitheness studio to successfully produce theatrical feature films. The bulk of the animation manufacture was (and still is) located in Los Angeles, and Pixar is located 350 miles (560 km) north in the San Francisco Bay Area. Traditional manus-fatigued animation was nevertheless the ascendant medium for feature animated films.[ citation needed ]

With the scarcity of Los Angeles-based animators willing to move their families so far northward to give upward traditional blitheness and try computer animation, Pixar'south new hires at this fourth dimension either came directly from college or had worked exterior characteristic animation. For those who had traditional animation skills, the Pixar animation software Marionette was designed so that traditional animators would require a minimum amount of grooming before condign productive.[78]

In an interview with PBS talk testify host Tavis Smiley,[79] Lasseter said that Pixar'due south films follow the same theme of self-improvement as the company itself has: with the assist of friends or family, a character ventures out into the real earth and learns to capeesh his friends and family. At the core, Lasseter said, "it's gotta be about the growth of the main character and how he changes."[79]

Role player John Ratzenberger, who had previously starred in the tv serial Cheers, has voiced a graphic symbol in every Pixar feature flick from Toy Story through Onward. He does not take a role in Soul, Luca and Turning Ruddy; however, a non-speaking background character in Soul bears his likeness. Pixar paid tribute to Ratzenberger in the cease credits of Cars (2006) by parodying scenes from three of its before films (Toy Story, Monsters, Inc., and A Bug's Life), replacing all of the characters with motor vehicle versions of them and giving each film an automotive-based title. Subsequently the 3rd scene, Mack (his character in Cars) realizes that the same actor has been voicing characters in every film.

Due to the traditions that accept occurred within the films and shorts such every bit anthropomorphic creatures and objects, and easter egg crossovers between films and shorts that have been spotted past Pixar fans, a blog post titled The Pixar Theory was published in 2013 by Jon Negroni, and popularized by the YouTube aqueduct Super Carlin Brothers,[80] proposing that all of the characters within the Pixar universe were related, surrounding Boo from Monsters Inc. and the Witch from Brave (2012).[81] [82] [83]

Additionally, Pixar is known for their films having expensive budgets, ranging from $150-200 million. Some of their films include Ratatouille, Toy Story iii, Toy Story four, Incredibles 2, Soul, The Good Dinosaur, Onward, and Turning Red.

Sequels and prequels [edit]

Toy Story 2 was originally commissioned by Disney as a 60-minute directly-to-video film. Expressing doubts about the forcefulness of the material, John Lasseter convinced the Pixar team to starting time from scratch and make the sequel their third total-length characteristic motion-picture show.

Following the release of Toy Story 2 in 1999, Pixar and Disney had a gentlemen'south understanding that Disney would not make any sequels without Pixar's involvement though retaining a right to do then. Later the 2 companies were unable to agree on a new deal, Disney announced in 2004 they would plan to motion forward on sequels with or without Pixar and put Toy Story 3 into pre-production at Disney's then-new CGI division Circle Seven Animation. However, when Lasseter was placed in charge of all Disney and Pixar animation following Disney's acquisition of Pixar in 2006, he put all sequels on hold and Toy Story iii was canceled. In May 2006, information technology was appear that Toy Story iii was back in pre-production with a new plot and under Pixar'due south control. The film was released on June eighteen, 2010, as Pixar's eleventh feature picture.

Shortly subsequently announcing the resurrection of Toy Story iii, Lasseter fueled speculation on further sequels by saying, "If we have a great story, we'll do a sequel."[84] Cars ii, Pixar'southward first non-Toy Story sequel, was officially announced in Apr 2008 and released on June 24, 2011, every bit their 12th. Monsters University, a prequel to Monsters, Inc. (2001), was appear in April 2010 and initially set for release in November 2012;[85] the release date was pushed to June 21, 2013, due to Pixar's past success with summer releases, according to a Disney executive.[86]

In June 2011, Tom Hanks, who voiced Woody in the Toy Story series, implied that Toy Story four was "in the works", although it had non however been confirmed by the studio.[87] [88] In April 2013, Finding Dory, a sequel to Finding Nemo, was announced for a June 17, 2016 release.[89] In March 2014, Incredibles ii and Cars iii were announced as films in development.[xc] In November 2014, Toy Story 4 was confirmed to be in development with Lasseter serving equally director.[91] However, in July 2017, Lasseter announced that he had stepped downward, leaving Josh Cooley as sole director.[92] Released in June 2019, Toy Story iv ranks among the 40 top-grossing films in American cinema.[93]

Adaptation to television [edit]

Toy Story is the showtime Pixar film to be adapted for television set equally Buzz Lightyear of Star Command film and Boob tube series on the UPN idiot box network, now The CW. Cars became the second with the aid of Cars Toons, a series of 3-to-5-minute short films running between regular Disney Aqueduct show intervals and featuring Mater from Cars.[94] Between 2013 and 2014, Pixar released its showtime 2 television specials, Toy Story of Terror! [95] and Toy Story That Time Forgot. Monsters at Work, a tv series spin-off of Monsters, Inc., premiered in July 2021, on Disney+.[96] [97]

On December ten, 2020, it was announced that iii series would be released on Disney+. The starting time is Dug Days (featuring Dug from Up) where Dug explores suburbia. Dug Days premiered on September i, 2021.[98] Side by side, a Cars show, titled Cars on the Route, was announced to come to Disney+ in Fall 2022 where it follows Mater and Lightning McQueen as they go on a road trip.[98] [99] Lastly, an original show entitled Win or Lose would be released on Disney+ in Autumn 2023. The series will follow a middle school softball squad the calendar week leading upward to the big title game where each episode volition exist from a dissimilar perspective.[98]

2D animation and live-action [edit]

All Pixar films and shorts to date take been reckoner-animated features, but and then far, WALL-E (2008) has been the only Pixar film not to exist completely animated as it featured a minor amount of live-action footage including Hello, Dolly! while Day & Night (2010), Kitbull (2019), Burrow (2020), and 20 Something (2021) are the only four shorts to characteristic 2d blitheness. 1906, the alive-action flick by Brad Bird based on a screenplay and novel by James Dalessandro about the 1906 earthquake, was in development but has since been abased past Bird and Pixar. Bird has stated that he was "interested in moving into the live-activeness realm with some projects" while "staying at Pixar [because] it's a very comfortable environment for me to work in". In June 2018, Bird mentioned the possibility of adapting the novel equally a Television set series, and the convulsion sequence equally a live-activity feature film.[100]

The Toy Story Toons short Hawaiian Holiday (2011) also includes the fish and shark as live-activity.

Jim Morris, president of Pixar, produced Disney'south John Carter (2012) which Andrew Stanton co-wrote and directed.[101]

Pixar's creative heads were consulted to fine tune the script for the 2011 live-activeness motion picture The Muppets.[102] Similarly, Pixar assisted in the story development of Disney's The Jungle Book (2016) as well as providing suggestions for the moving picture's end credits sequence.[103] Both Pixar and Mark Andrews were given a "Special Thank you" credit in the film's credits.[104] Additionally, many Pixar animators, both one-time and current, were recruited for a traditional manus-drawn blithe sequence for the 2018 film Mary Poppins Returns.[105]

Pixar representatives take likewise assisted in the English language localization of several Studio Ghibli films, mainly those from Hayao Miyazaki.[106]

In 2019, Pixar developed a live-action subconscious camera reality show, titled Pixar in Existent Life, for Disney+.[107]

Upcoming films [edit]

Four upcoming films have been announced. The outset, titled Lightyear, which is written and directed by Angus MacLane, will exist released on June 17, 2022,[108] [109] followed past three untitled films on June 16, 2023,[110] March 1, 2024, and June 21, 2024.[111]

Co-op Programme [edit]

The Pixar Co-op Program, a part of the Pixar University professional development program, allows their animators to employ Pixar resources to produce independent films.[112] [113] The start 3D project accepted to the program was Borrowed Time (2016); all previously accepted films were live-activeness.[114]

Franchises [edit]

This is non including the associated productions from the Pixar media.

| Titles | Films | Short films | Telly series | Release Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toy Story | v | 4 | 2 | 1995–present |

| Monsters, Inc. | 2 | 2 | i | 2001–present |

| Finding Nemo | 2 | ii | 0 | 2003–present |

| The Incredibles | three | 3 | 0 | 2004–present |

| Cars | iii | 5 | two | 2006–present |

Exhibitions [edit]

Since December 2005, Pixar has held a variety of exhibitions celebrating the art and artists of the organization and its contribution to the world of animation.[115]

Pixar: 20 Years of Animation [edit]

Upon its 20th anniversary, in 2006, Pixar celebrated with the release of its seventh feature moving picture Cars, and held two exhibitions from April to June 2010 at Science Middle Singapore in Jurong Eastward, Singapore and the London Science Museum in London.[116] It was their start time holding an exhibition in Singapore.[ commendation needed ]

The exhibition highlights consist of work-in-progress sketches from various Pixar productions, clay sculptures of their characters and an autostereoscopic short showcasing a 3D version of the exhibition pieces which is projected through 4 projectors. Another highlight is the Zoetrope, where visitors of the exhibition are shown figurines of Toy Story characters "animated" in existent-life through the zoetrope.[116]

Pixar: 25 Years of Animation [edit]

Pixar historic its 25th anniversary in 2011 with the release of its twelfth feature motion-picture show Cars two, and held an exhibition at the Oakland Museum of California from July 2010 until Jan 2011.[117] The exhibition tour debuted in Hong Kong and was held at the Hong Kong Heritage Museum in Sha Can from March 27 to July xi, 2011.[118] [119] In 2013, the exhibition was held in the EXPO in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. For 6 months from July 6, 2012, until January 6, 2013, the city of Bonn (Germany) hosted the public showing,[120]

On November sixteen, 2013, the exhibition moved to the Art Ludique museum in Paris, France with a scheduled run until March two, 2014.[121] The exhibition moved to three Spanish cities subsequently in 2014 and 2015: Madrid (held in CaixaForum from March 21 until June 22),[122] Barcelona (held too in Caixaforum from February until May) and Zaragoza.[123]

Pixar: 25 Years of Blitheness includes all of the artwork from Pixar: 20 Years of Animation, plus art from Ratatouille, WALL-E, Upwardly and Toy Story 3.[ commendation needed ]

The Science Behind Pixar [edit]

The Science Behind Pixar is a travelling exhibition that showtime opened on June 28, 2015, at the Museum of Scientific discipline in Boston, Massachusetts. It was adult by the Museum of Scientific discipline in collaboration with Pixar. The exhibit features forty interactive elements that explain the production pipeline at Pixar. They are divided into eight sections, each demonstrating a stride in the filmmaking process: Modeling, Rigging, Surfaces, Sets & Cameras, Animation, Simulation, Lighting, and Rendering. Before visitors enter the exhibit, they sentry a short video at an introductory theater showing Mr. Ray from Finding Nemo and Roz from Monsters, Inc..[ citation needed ]

The exhibition closed on Jan ten, 2016, and was moved to the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania where it ran from March 12 to September 5. Afterwards, it moved to the California Scientific discipline Center in Los Angeles, California and was open from Oct 15, 2016, to April ix, 2017. It fabricated another stop at the Scientific discipline Museum of Minnesota in St. Paul, Minnesota from May 27 through September 4, 2017.[124]

The exhibition opened in Canada on July 1, 2017, at the TELUS World of Science – Edmonton (TWOSE).[ citation needed ]

Pixar: The Design of Story [edit]

Pixar: The Design of Story was an exhibition held at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City from October 8, 2015, to September eleven, 2016.[125] [126] The museum too hosted a presentation and conversation with John Lasseter on November 12, 2015, entitled "Blueprint Past Hand: Pixar's John Lasseter".[125]

Pixar: thirty Years of Blitheness [edit]

Pixar celebrated its 30th anniversary in 2016 with the release of its seventeenth feature moving-picture show Finding Dory, and put together another milestone exhibition. The exhibition offset opened at the Museum of Contemporary Fine art in Tokyo, Nihon from March 5, 2016, to May 29, 2016. Information technology subsequently moved to the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum National Museum of History, Dongdaemun Design Plaza where it ended on March v, 2018, at the Hong Kong Heritage Museum.[127]

Legacy [edit]

Pixar has a strong legacy with its reach on many unlike generations. Its emotional depth combined with its playfulness integrated in a cutting-edge technology has left it with a lasting legacy amidst children and developed viewers. With Pixar's success, many take considered it an integral office of what it means to be a child, which may contribute to its popularity in an often separate adult audition. From the 1990s to the present, Pixar movies have become a central forcefulness in blitheness.[128] Discover Magazine wrote:

The message hidden within Pixar'southward magnificent films is this: humanity does non have a monopoly on personhood. In whatever form non- or super-human being intelligence takes, it will need brave souls on both sides to defend what is right. If we tin can live up to this burden, humanity and the world we live in will exist better for it.[128]

Meet also [edit]

- The Walt Disney Company

- Disney's Nine Old Men

- 12 basic principles of blitheness

- Walt Disney Treasures

- Disney Blitheness: The Illusion of Life

- Modern blitheness in the United States: Disney

- Animation studios endemic by The Walt Disney Company

- Walt Disney Animation Studios

- Disneytoon Studios

- Blueish Sky Studios

- 20th Century Blitheness

- List of Disney theatrical animated characteristic films

References [edit]

- ^ a b "Company FAQS". Pixar. Archived from the original on July 2, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d e f Smith, Alvy Ray. "Pixar Founding Documents". Alvy Ray Smith Homepage. Archived from the original on April 27, 2005. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ^ Smith, Alvy Ray. "Proof of Pixar Cofounders" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved Dec 23, 2015.

- ^ "Walt Disney Company, Form 8-Yard, Electric current Report, Filing Date Jan 26, 2006" (PDF). secdatabase.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ^ a b "Walt Disney Company, Form 8-Thousand, Electric current Study, Filing Date May viii, 2006". secdatabase.com. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ^ "Pixar". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on Baronial 29, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ When added to foreign grosses Pixar Movies at the Box Office Box Role Mojo

- ^ "Brief History of the New York Establish of Engineering Computer Graphics Lab". Carnegie Mellon University. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ "Loonshots: How to Nurture the Crazy Ideas That Win Wars, Cure Diseases, and Transform Industries". Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Story Behind Pixar – with Alvy Ray Smith". mixergy.com. Archived from the original on December 26, 2015. Retrieved Dec 25, 2015.

- ^ Sito, Tom (2013). Moving Innovation: A History of Reckoner Animation. p. 137. ISBN9780262019095. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved Oct 3, 2020.

- ^ "CGI Story: The Development of Computer Generated Imaging". lowendmac.com. June 8, 2014. Archived from the original on November 25, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ "ID 797 – History of Estimator Graphics and Animation". Ohio State Academy. Archived from the original on January 10, 2016. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ a b Hormby, Thomas (January 22, 2007). "The Pixar Story: Fallon Forbes, Dick Shoup, Alex Schure, George Lucas and Disney". Low Stop Mac. Archived from the original on August xiv, 2013. Retrieved March one, 2007.

- ^ Smith, Alvy Ray (August xv, 1995). "Alpha and the History of Digital Compositing" (PDF). Princeton University—Department of Figurer Science. Archived (PDF) from the original on August ten, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- ^ "Everything You E'er Saw | Reckoner Graphics World". www.cgw.com. 32. February 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ "What will Pixar's John Lasseter practise at Disney – May. 17, 2006". annal.fortune.com. Archived from the original on September 29, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ Jones, Brian Jay (2016). George Lucas: A Life. New York City: Piddling, Brown and Company. pp. 289–90. ISBN978-0316257442.

- ^ "Alvy Pixar Myth three". alvyray.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2015. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

- ^ "Pixar Selects Silicon Graphics Octane2 Workstations". HPCwire. July 28, 2000. Retrieved Nov xi, 2021.

- ^ Coll, Steve (October 1, 1984). "When The Magic Goes". Inc. Archived from the original on June xxx, 2017. Retrieved March v, 2017.

- ^ "An exclusive interview with Daniel Kottke". India Today. September 13, 2011. Archived from the original on May 6, 2012. Retrieved Oct 27, 2011.

- ^ Oates, Sarah (July xv, 1985). "Chuck Eastward. Cheese Gets New Lease on Life". Washington Postal service. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved January one, 2022.

- ^ Kieron Johnson (April 28, 2017). "Pixar's Co-Founders Heard 'No' 45 Times Earlier Steve Jobs Said 'Yes'". Entrepreneur.com. Archived from the original on Oct 23, 2020. Retrieved Apr 11, 2018.

- ^ Paik 2015, p. 52.

- ^ Smith, Alvy Ray (Apr 17, 2013). "How Pixar Used Moore's Constabulary to Predict the Time to come". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on June 26, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ Cost, David A. (Nov 22, 2008). "Pixar's film that never was: "Monkey"". The Pixar Touch. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved February thirteen, 2019.

- ^ "Beginning fully digital characteristic flick". Guinness Globe Records. Guinness World Records Limited. Retrieved Oct 30, 2021.

- ^ Taylor, Drew (December 16, 2020). "'The Rescuers Down Under': The Untold Story of How the Sequel Changed Disney Forever". Collider . Retrieved October xxx, 2021.

- ^ a b "Pixar Animation Studios". Ohio Country University. Archived from the original on July 3, 2017. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ Paik, Karen (November 3, 2015). To Infinity and Beyond!: The Story of Pixar Animation Studios. Chronicle Books. p. 58. ISBN9781452147659. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved Baronial 18, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Toy Stories and Other Tales". University of Saskatchewan. Archived from the original on August seven, 2017. Retrieved Baronial xviii, 2017.

- ^ "Pixar Animation Studios—Visitor History". Fundinguniverse.com. Archived from the original on March iv, 2012. Retrieved July eight, 2011.

- ^ "History of Computer Graphics: 1990–99". Hem.passagen.se. Archived from the original on Apr 18, 2005. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ Fisher, Lawrence Grand. (April two, 1991). "Hard Times For Innovator in Graphics". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 15, 2018. Retrieved July eight, 2011.

- ^ "The Illusion and Emotion Backside 'Toy Story four' – Newsweek". Newsweek. July 5, 2019. Archived from the original on July xix, 2019. Retrieved July twenty, 2019.

- ^ Calonius, Erik (March 31, 2011). Ten Steps Ahead: What Smart Business People Know That You Don't. Headline. p. 68. ISBN9780755362363. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Cost, David A. (2008). The Pixar Touch: The making of a Company (1st ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 137. ISBN9780307265753.

- ^ Schlender, Brent (September eighteen, 1995). "Steve Jobs' Amazing Flick Chance Disney Is Betting on Computerdom's Ex-Boy Wonder to Evangelize This Year's Animated Christmas Blockbuster. Tin can He Practice for Hollywood What He Did for Silicon Valley?". CNNMoney. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved August iii, 2020.

- ^ Nevius, C.W. (August 23, 2005). "Pixar tells story backside 'Toy Story'". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ "Toy Story" Archived Baronial 12, 2019, at the Wayback Auto. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ <Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson, folio 291> "Company FAQ'southward". Pixar. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ a b Catmull, Ed (March 12, 2014). "Inside The Pixar Braintrust". Fast Visitor. Mansueto Ventures, LLC. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- ^ Wloszczyna, Susan (October 31, 2012). "'Wreck-It Ralph' is a Disney animation game-changer". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ Swimming, Steve (February 21, 2014). "Why Disney Fired John Lasseter—And How He Came Dorsum to Heal the Studio". The Wrap. Archived from the original on April seven, 2014. Retrieved Apr 5, 2014.

- ^ Hartl, John (July 31, 2000). "Sequels to 'Toy Story,' 'Tail,' 'Dragonheart' become straight to video". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on September 28, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Pixar dumps Disney". CNNMoney. January 29, 2004. Archived from the original on May 12, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- ^ "Pixar Says 'So Long' to Disney". Wired. Jan 29, 2004. Archived from the original on May two, 2008. Retrieved Apr 22, 2008.

- ^ a b Grover, Ronald (December 9, 2004). "Steve Jobs's Precipitous Turn with Cars". Business organization Week. Archived from the original on March xi, 2007. Retrieved February 23, 2007.

- ^ "Pixar Perfectionists Cook Up 'Ratatouille' Equally Latest Blithe Concoction". Star Pulse. Archived from the original on October 27, 2007. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ La Monica, Paul R. (January 24, 2006). "Disney buys Pixar". CNN. Archived from the original on March 3, 2020. Retrieved August iii, 2020.

- ^ a b Holson, Laura One thousand. (Jan 25, 2006). "Disney Agrees to Acquire Pixar in a $7.iv Billion Deal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 12, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ La Monica, Paul R. (January 24, 2006). "Disney buys Pixar". CNN. Archived from the original on March 3, 2020. Retrieved Apr 22, 2008.

- ^ a b c Schlender, Brent (May 17, 2006). "Pixar's magic human being". CNN. Archived from the original on July fifteen, 2012. Retrieved Apr 20, 2012.

- ^ Issacson, Walter (2013). Steve Jobs (1st paperback ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 439. ISBN9781451648546.

- ^ Issacson, Walter (2013). Steve Jobs (1st paperback ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 438. ISBN9781451648546.

- ^ "Agreement and Plan of Merger by and amid The Walt Disney Visitor, Lux Acquisition Corp. and Pixar". Securities and Exchange Commission. January 24, 2006. Archived from the original on April 14, 2010. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ^ Bunk, Matthew (January 21, 2006). "Sale unlikely to change Pixar culture". Inside Bay Area. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ Graser, Marc (September ten, 2008). "Morris and Millstein named managing director of Disney studios". Variety. Archived from the original on September xiv, 2008. Retrieved September x, 2008.

- ^ Kilday, Gregg (Dec 4, 2013). "Pixar vs. Disney Animation: John Lasseter'southward Catchy Tug-of-War". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on Feb ten, 2020. Retrieved Dec iv, 2013.

- ^ a b c Bell, Chris (April v, 2014). "Pixar's Ed Catmull: interview". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on April half-dozen, 2014. Retrieved Apr v, 2014.

- ^ a b c Zahed, Ramin (Apr 2, 2012). "An Interview with Disney/Pixar President Dr. Ed Catmull". Animation Magazine. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ "Pixar Canada sets up home base of operations in Vancouver, looks to expand". The Vancouver Sun. Canada. Archived from the original on Apr 22, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ "Pixar Canada shuts its doors in Vancouver". The Province. Oct 8, 2013. Archived from the original on April 24, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Graser, Marc (November 18, 2014). "Walt Disney Blitheness, Pixar Promote Andrew Millstein, Jim Morris to President". Diversity. Penske Business Media. Archived from the original on November 21, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ^ Masters, Kim (November 21, 2017). "John Lasseter's Pattern of Alleged Misconduct Detailed by Disney/Pixar Insiders". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 21, 2017. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- ^ Zeitchik, Steven (November 21, 2017). "Disney animation guru John Lasseter takes go out afterwards sexual misconduct allegations". The Washington Mail service. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ Masters, Kim (April 25, 2018). "He Who Must Non Be Named": Can John Lasseter Ever Return to Disney?". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 3, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks (June 8, 2018). "Pixar Co-Founder to Leave Disney After 'Missteps'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 9, 2018. Retrieved June eight, 2018.

- ^ Kit, Borys (June 19, 2018). "Pete Docter, Jennifer Lee to Lead Pixar, Disney Animation". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Kit, Borys (Oct 23, 2018). "Pixar Co-Founder Ed Catmull to Retire". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 24, 2018. Retrieved Oct 24, 2018.

- ^ Kit, Borys (January 18, 2019). "'Toy Story iii,' 'Coco' Director Lee Unkrich Leaving Pixar Later on 25 Years (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January nineteen, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ Pimentel, Benjamin (Baronial 28, 2000). "Lucasfilm Unit Looking at Movement To Richmond / Pixar shifting to Emeryville". San Francisco Relate. Archived from the original on Feb 2, 2015.

- ^ "Bohlin Cywinski Jackson | Pixar Animation Studios". Bohlin Cywinski Jackson. Archived from the original on Baronial 30, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ^ "Pixar Animation Studios, The Steve Jobs Edifice". Auerbach Consultants.

- ^ OpenEdition: Hollywood and the Digital Revolution Archived May 11, 2018, at the Wayback Auto by Alejandro Pardo [in French]

- ^ Julia Robinson Mathematics Festival 2008 Archived May 11, 2018, at the Wayback Automobile Mathematical Sciences Research Institute

- ^ a b Hormby, Thomas (January 22, 2007). "The Pixar Story: Fallon Forbes, Dick Shoup, Alex Schure, George Lucas and Disney". Low End Mac. Archived from the original on August 14, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ^ a b Smiley, Tavis (January 24, 2007). "Tavis Smiley". PBS. Archived from the original on Nov 24, 2007. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ^ "JonNegroni : The Pixar Theory Fence, Featuring SuperCarlinBros". June 27, 2016. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Dunn, Gaby (July 12, 2013). ""Pixar Theory" connects all your favorite movies in 1 universe". The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on August 20, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ Whitney, Erin (July 12, 2013). "The (Mind-Blowing) Pixar Theory: Are All the Films Connected?". Moviefone. Archived from the original on July fifteen, 2013. Retrieved July thirteen, 2013.

- ^ McFarland, Kevin (July 12, 2013). "Read This: A m unified theory connects all Pixar films in one timeline". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on July 15, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ Douglas, Edwards (June iii, 2006). "Pixar Mastermind John Lasseter". comingsoon.net. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ^ "Disney announce Monsters Inc sequel". BBC News. Apr 23, 2010. Archived from the original on September 13, 2019. Retrieved Apr 23, 2010.

- ^ "Monsters Academy Pushed to 2013". movieweb.com. April 4, 2011. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- ^ "Tom Hanks reveals Toy Story 4". Digital Spy. June 27, 2011. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2007.

- ^ Access Hollywood June 27, 2011

- ^ Keegan, Rebecca (September 18, 2013). "'The Practiced Dinosaur' moved to 2015, leaving Pixar with no 2014 film". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 19, 2013. Retrieved September xviii, 2013.

- ^ Vejvoda, Jim (March xviii, 2014). "Disney Officially Announces The Incredibles 2 and Cars 3 Are in the Works". IGN. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved March xviii, 2014.

- ^ Ford, Rebecca (November 6, 2014). "John Lasseter to Straight Fourth 'Toy Story' Film". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ Khatchatourian, Maane (July 14, 2017). "'Toy Story iv': Josh Cooley Becomes Sole Director as John Lasseter Steps Downwards". Multifariousness. Archived from the original on July 15, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ^ "U.S. Box Role: 'Toy Story 4' Among 40 Top-Grossing Movies Ever". Forbes. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ "Cars Toons Coming in October To Disney Channel". AnimationWorldNetwork. September 26, 2008. Retrieved Dec 4, 2008.

- ^ Cheney, Alexandra (October xiii, 2013). "Watch A Clip from Pixar'southward Kickoff TV Special 'Toy Story OF TERROR!'". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved Feb 24, 2014.

- ^ Littleton, Cynthia (Nov 9, 2017). "New 'Star Wars' Trilogy in Works With Rian Johnson, TV Series Also Coming to Disney Streaming Service". Archived from the original on November 10, 2017. Retrieved Dec 11, 2017.

- ^ Goldberg, Lesley (April 9, 2019). "'Monsters, Inc.' Vox Cast to Render for Disney+ Series (Sectional)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April nine, 2019. Retrieved April ix, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Three New Pixar Series Coming to Disney+, Including the Very Adorable 'Up' Spin-Off 'Dug Days'". /Film. December 11, 2020. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ Del Rosario, Alexandra (November 12, 2021). "Disney+'s 'Cars' Serial Gets Title, 'Tiana' Enlists Stella Meghie Equally Writer/Director; Start-Look Images Released". Deadline Hollywood . Retrieved November fourteen, 2021.

- ^ Adam Chitwood (June 18, 2018). "Brad Bird Says '1906' May Go Made as an "Amalgam" of a TV and Film Project". Collider. Archived from the original on June 18, 2018. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ Jagernauth, Kevin (February 16, 2012). "'John Carter' Producer Jim Morris Confirms Sequel 'John Carter: The Gods Of Mars' Already In The Works". The Playlist. Indiewire.com. Archived from the original on Jan 22, 2015. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ^ Kit, Borys (Oct 14, 2010). "Disney Picks Pixar Brains for Muppets Movie". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 25, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ Taylor, Drew. "9 Things Disney Fans Demand to Know Virtually The Jungle Book, According to Jon Favreau". Disney Insider. The Walt Disney Company. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ^ "The Jungle Book: Press Kit" (PDF). wdsmediafile.com. The Walt Disney Studios. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 26, 2019. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "Mary Poppins Returns – Press Kit" (PDF). wdsmediafile.com. Walt Disney Studios. Retrieved November 29, 2018. [ permanent expressionless link ]

- ^ TURAN, KENNETH (September 20, 2002). "Nether the Spell of 'Spirited Away'". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on June 19, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ Palmer, Roger (Baronial 27, 2019). "'Pixar in Real Life' Coming Soon To Disney+". What's On Disney Plus. Archived from the original on November 2, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ Milligan, Mercedes (March i, 2018). "Disney Pushes Alive 'Mulan' to 2020, Dates Multi-Studio Slate". Blitheness Magazine. Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved March v, 2018.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (December 10, 2020). "Pixar Has Fizz Lightyear Origin Movie In Works With Chris Evans & 'Turning Red' From 'Bao' Filmmaker Domee. Shi". borderline.com. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ^ "Disney Dates a Ton of Pics into 2023 & Juggles Fox Releases with Ridley Scott's 'The Terminal Duel' to Open Christmas 2020, 'The King's Man' Next Fall – Update". November xvi, 2019. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Kit, Borys (September ten, 2021). "Disney's Alive-Action 'The Little Mermaid' to Open on Memorial Day Weekend in 2023". The Hollywood Reporter . Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ^ Hill, Libby (October 17, 2016). "2 Pixar animators explore the depths of grief and guilt in 'Borrowed Fourth dimension'". LA Times. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ Desowitz, Bill (Oct 24, 2016). "'Borrowed Time': How Two Pixar Animators Made a Daring, Off-Brand Western Brusk". Indiewire. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ Failes, Ian (July 29, 2016). "How Andrew Coats and Lou Hamou-Lhadj Fabricated The Independent Curt 'Borrowed Time' Inside Pixar". Cartoon Mash. Archived from the original on Feb two, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "Pixar: 20 Years of Animation". Pixar. Archived from the original on January eight, 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ a b Eng Eng, Wang (April one, 2010). "Pixar animation comes to life at Science Centre exhibition". MediaCorp Channel NewsAsia. Archived from the original on April 4, 2010. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ "Pixar: 25 Years of Animation". Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved Jan 11, 2011.

- ^ "Pixar: 25 Years of Animation". Leisure and Cultural Services Department. Archived from the original on Feb 17, 2011. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ^ "Pixar brings fascinating animation earth to Hong Kong Archived August 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Xinhua, March 27, 2011

- ^ GmbH, Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Federal republic of germany. "Pixar – Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland – Bonn". world wide web.bundeskunsthalle.de. Archived from the original on December 4, 2017. Retrieved Dec 3, 2017.

- ^ "Exposition Pixar" (in French). Art Ludique. Archived from the original on Dec 21, 2014. Retrieved December thirty, 2014.

- ^ "Pixar: 25 años de animación". Obra Social "la Caixa". Archived from the original on January 24, 2014. Retrieved Apr 24, 2014.

- ^ ""Pixar. 25 years of animation" Exhibition in Kingdom of spain". motionpic.com. Archived from the original on December 31, 2014. Retrieved Dec xxx, 2014.

- ^ "The Scientific discipline Behind Pixar at pixar.com". Archived from the original on July 8, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ a b "Pixar: The Design of Story". Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum. October 8, 2015. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Cooper Hewitt to Host Pixar Exhibition". The New York Times. July 26, 2015. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018. Retrieved March v, 2018.

- ^ "Pixar: 30 Years Of Blitheness". Pixar Animation Studios. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018. Retrieved Apr 10, 2018.

- ^ a b "The Subconscious Message in Pixar's Films". Detect Magazine . Retrieved April 3, 2022.

External links [edit]

- Official website

- Pixar'due south channel on YouTube

- Pixar Animation Studios at The Large Drawing DataBase

- List of the twoscore founding employees of Pixar

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pixar

Posted by: giesenappy1975.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Item Serves As The Mascot For Pixar Animation Studios?"

Post a Comment